A jet engine is a machine that converts energy, rich liquid fuel into a powerful thrust called thrust. The thrust of one or more engines pushes the aircraft forward, forcing the air through its scientifically shaped wings, creating an upward force called “lift” that pushes it toward the sky.

One way to understand modern jet engines is to compare them with the piston engines used in early airplanes, which are very similar to the piston engines still used in cars. Piston engines (also called reciprocating engines because the pistons move back and forth or “reciprocate”) play a role in a solid steel “cooking pot” called a cylinder. Fuel is injected into the cylinder along with the air in the atmosphere. The piston in each cylinder compresses the mixture, increasing the temperature of the mixture, causing it to self-ignite (in a diesel engine) or ignite it with the aid of a spark plug (in a gasoline engine). Before the entire four-step cycle (intake, compression, combustion, exhaust) repeats, the burning fuel and air explode and expand, pushing the piston backwards and driving the crankshaft that powers the car wheels (or airplane propellers). The trouble with this is that the piston is only driven in one of the four steps, so it generates power in only a small part of the time.

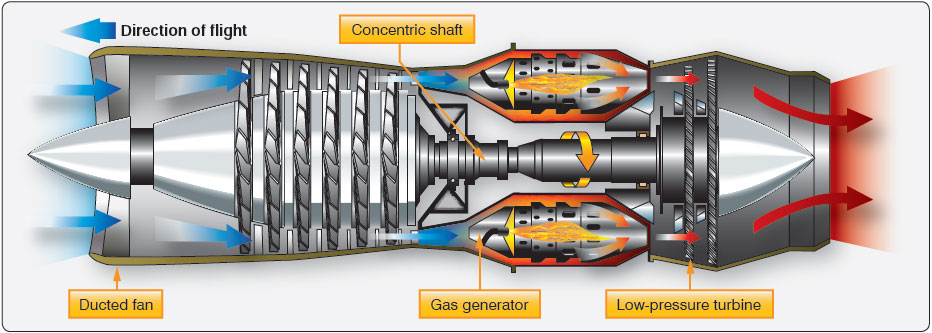

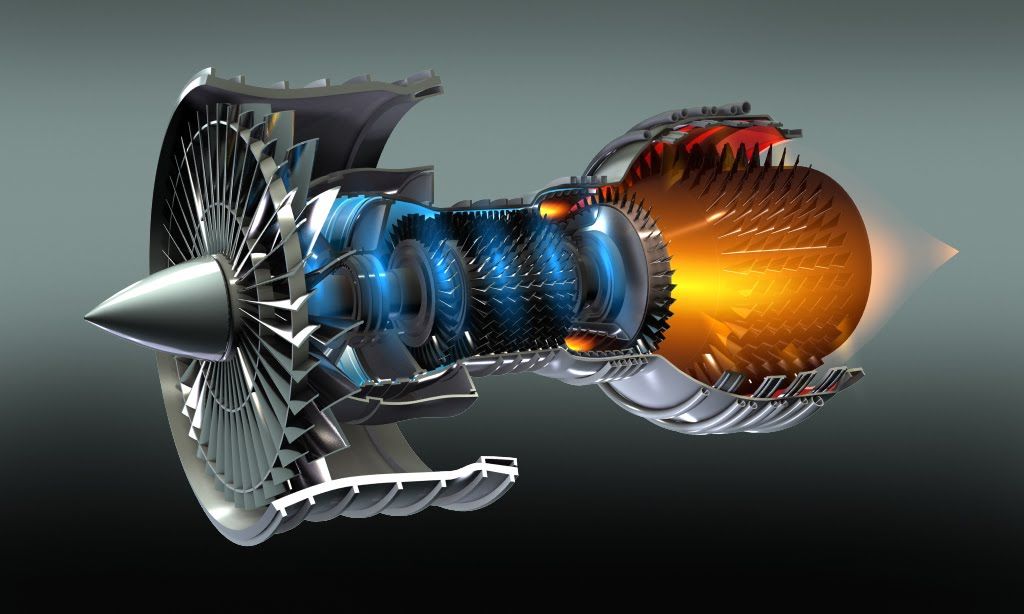

The power produced by a piston engine is directly related to the size of the cylinder and the distance the piston moves. Unless you use bulky cylinders and pistons (or many of them), you can only generate a relatively small amount of power. If your piston engine powers the aircraft, it will limit its flight speed, flight capacity, flight capacity and carrying capacity. Jet engines use the same scientific principles as car engines: it burns fuel with air (a chemical reaction, called combustion), to release energy to power airplanes, vehicles, or other machines. However, instead of using a cylinder that goes through four steps in sequence, it uses a long metal tube that performs the same four steps in a straight line sequence. This is a thrust production line! In the simplest type of jet engine, called a turbojet, air is drawn in at the front through an inlet (or intake), compressed by a fan, mixed with fuel and combusted, and then fired out as a hot, fast moving exhaust at the back.

A basic principle of physics is called the law of conservation of energy. It tells us that if a jet engine needs to produce more power per second, it must burn more fuel per second. A jet engine is carefully designed to emit a large amount of air and burn it with a large amount of fuel (roughly 50 parts air to one part fuel), so the main reason for producing more power is because it can burn more fuel. fuel. Since intake, compression, combustion, and exhaust occur simultaneously, the jet engine always maintains maximum power (unlike a single cylinder in a piston engine). Unlike piston engines, which use a single stroke of the piston to extract energy, a typical jet engine passes its exhaust gas through multiple turbine “stages” to extract as much energy as possible. This makes it more efficient (it gets more power from the same quality of fuel).

A more specialized name for a jet engine is gas turbine, although it is not very clear what this means, but in fact, it is a better description of how this engine works. The working principle of a jet engine is to burn fuel in the air to release hot exhaust gas. However, when a car engine uses exhaust gas explosion to push its pistons, a jet engine forces the gas to pass through the blades of a windmill-shaped rotating wheel (turbine) to make it rotate. Therefore, in a jet engine, the exhaust gas powers the turbine, hence the name “gas turbine”. When we talk about jet engines, we tend to think of rocket-like tubes that shoot exhaust gas backwards. Another basic principle of physics is Newton’s third law of motion, which tells us that when the exhaust gas of a jet engine is injected backwards, the airplane itself must move forward. It’s like a skateboarder kicking backwards on the sidewalk. In jet engines, it is the exhaust gas that provides the “recoil.” In daily terms, the action (the force of the exhaust gas jetting backward) is equal and opposite to the reaction force (the force of the aircraft moving forward); the action moves the exhaust gas, and the reaction force moves the aircraft.

But not all jet engines work in this way: some jet engines produce almost no rocket exhaust. Instead, most of their power is used by the turbine-the shaft connected to the turbine is used to power the propeller (on a propeller plane), rotor blades (on a helicopter), and a giant fan (on a large passenger plane)) Or generators (in gas turbine power plants).

Stay with science and knowledge.

Halit Yusuf Genç

Sources: